Chapter 8

TOC Home Previous « Next » Glossary Off

Darkening Shadow

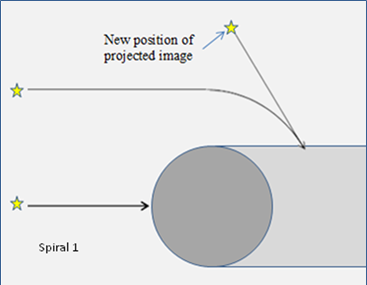

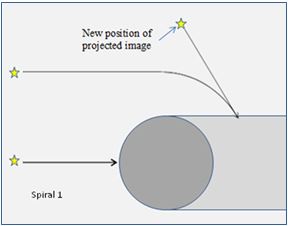

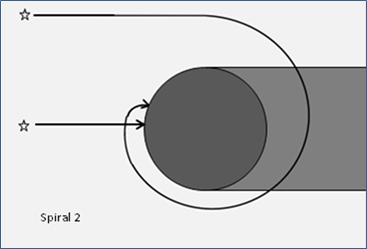

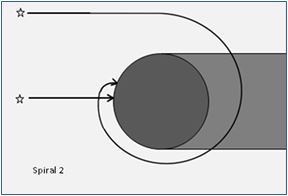

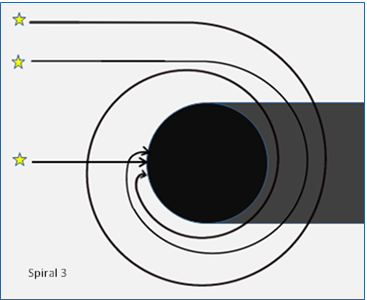

Let’s watch two flux vectors as the object on the leftabove becomes less transparent. That is, less flux makes its way through producing a darker shadow. The darker shadow influences the bending light beams even more which results in a longer arc. Actually, the arc is really the beginning of a spiral.

It’s unknown where a runaway condition will occur, but at some critical point, the light beam’s direction reverses, and the spiral continues to develop until it winds its way down to the object. The source of the light beam goes onto the surface, not around. Now instead of one beam there are two, and since light travels on flux, the force has doubled. The distance from the center of the object to the first spiral will become the inner event. Additional spirals quickly add even more vectors to the object’s surface and internal structure once the runaway begins.

Amplification of the superforce begins in earnest as more outer layer spirals come into play. The exterior spirals become known as outer events.

The greater the radius of events, the greater the amplifying power of the flux. The zone is spherical so the force grows exponentially as a sphere’s surface gets larger with an increase in its diameter. Thanks to the universe’s power of two rule, every time this influencing radius doubles, the additional force brought to bear on the object quadruples. Another word for this inner-outer zone is the event horizon.

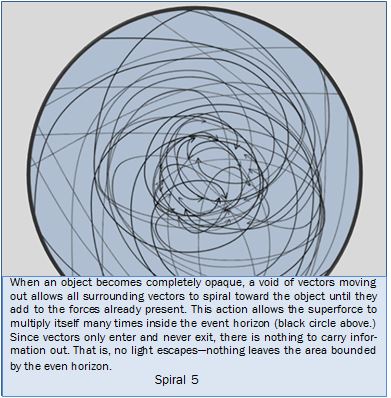

Now imagine what happens when an object becomes totally opaque. No flux can get through leaving a complete void of flux exiting the object. At this point all vectors are inbound. There is nothing to resist any object’s approach.

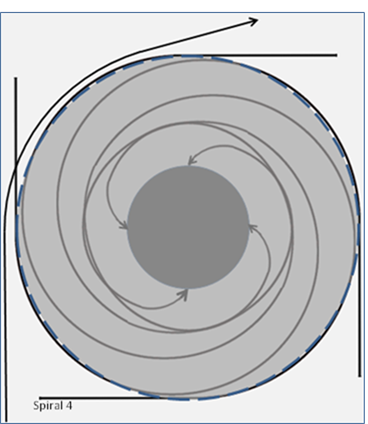

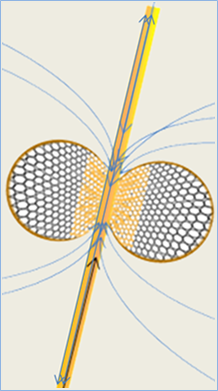

Spiral 4 represents a plane of four vectors, all swooping in adding their crushing contribution. Also shown is a single vector indicating that outside the event horizon, (dashed circle) they only bend to varying degrees depending on the distance from the boundary.

As the object becomes smaller and darker, the event horizon expands adding more force to the runaway condition. It’s something like feedback entering a microphone. The ears continue protesting until someone takes correct measures to fix it. But, there is no countermeasure for a black hole.

See Spiral 0 in chapter 7 again for an example of how flux vectors bend when an object’s transparency becomes too opaque. The missing vectors allow perpendicular and angular ones to bend the outer flux towards the void. Below, Spiral 5 is the extreme limit leading to additional forces exerting thousands of times more pressure on the object. It becomes a runaway condition leading to unknown endings. The event horizon does not have to be a globe. It may also be in the shape of an apple such that its poles are open to flux, incoming and outgoing. Some black holes eject streams of energy at its poles, so there is either a way in/out at the poles, or the energy escapes outside the horizon, perhaps in a form of a doughnut or torus. Outside the event horizon, the vectors do not wrap. They just bend to varying degrees.

A large galaxy or other massive units bend light beams such that supernova and other bright objects can be seen behind them. See Monica Young’s article Astronomers Predict a Supernova on Sky and Telescope’s web-site. It describes five separate images of the same supernova behind an elliptical galaxy.

Although light bending is an ongoing process, at first conception it could only be witnessed under certain conditions. Sir Arthur Eddington was among the first to verify Einstein’s theory of relativity when he setup an expedition to the island of Principe for the total solar eclipse of May 29, 1919. This experiment proved that flux vectors bend light rays. However, scientists insist on declaring that space bends the waves. Since gravity and space are linked, it is understandable how astronomers can come to the conclusion that space is what curves light instead of the superforce having its way with an absence of flux vectors. Also, not everyone is aware that light travels on superforce flux.

Neutron Stars

It’s difficult to imagine the earth crunched down to the size of a large apartment building. However, comparing the size of an atom with its electrons swinging around its nucleus to the nucleus with its electrons tucked neatly inside the protons presents a much different picture. The space used to accommodate electrons in orbit disappears. Remember, a proton with its electron tucked inside is a neutron, and neutrons love togetherness. The superforce has its way with these guys and crunches them with very little opposition. Once all the protons become neutrons, it makes sense how nature can pack them inside small places. When letting air out of bubble wrap it shrinks rather quickly.

After nature removes all the room taken up by an atom’s electrons, it’s much easier to imagine how millions of neutrons can replace a single atoms space. It varies quite a bit, but an atom’s diameter could be 10,000 times its nucleus’ diameter. Comparing the size of the sun to this nucleus means the outer limits of the solar system would lie just inside Neptune’s orbit: the edge would be 2,161,880,000 miles from the sun.

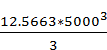

Using a sphere as an example even takes the example further. If we take an atom’s radius to its nucleus’ radius ratio of only 5,000:1 to calculate its volume, it would be,

volume of sphere

=

![]()

=

=

523,598,775,598

times more space to accommodate all that extra matter. That’s just over ½ trillion neutrons for every atom that once held that position, and over ½ trillion times more weight, and that is only one atom. How many trillions of atoms are in that star for neutrons to replace?

But this picture comes after the process that placed the electrons into the protons has occurred. That story is interesting, and you can learn how it takes place with a little research on the www.

This also brings on a question. Although an electron’s charge is neutralized when placed inside a neutron, does the law commanding it to release magnetic energy when in motion change? That is a very important question. If the electron is still required to emit magnetic flux while in motion, that is a whole lot of flux lying in wait in such a small space. Imagine over ½ trillion times more magnetic flux just for one atom’s worth of volume.

Do we need to rethink neutron stars and magnetars?

When an object spins, it tends to flatten, and the faster the spin, the flatter the object. As one might suspect, an object the size of Earth being squashed down to 1/1000th its size would spin 1,000 times faster at its surface using only momentum as a reference. Of course if a volume of material is considered, it becomes more complicated because that volume contains more material per cubic meter as it gets squashed. It becomes more dense.

Planets do not morph into neutron stars, but we’ll use the earth as an example for size reference. Say the earth rotates one thousand miles per hour (mph) at the equator, and it is 8000 miles in diameter. That means it rotates 1,000,000 mph when it shrinks down to eight miles wide. That is 11.57 revolutions per second. At this state, it is not a planet. It is not even matter as we know it because there are no electrons, no protons: just plain ’ole neutrons. A bunch of neutrons spinning round and round so fast each one needs to fly off in the current direction of travel. That direction is tangential to its rotation. That ever present superforce counters the centrifugal force attempting to outcast each piece of matter, so the outer neutrons can only go outwardly so far.

But what is happening to those near the poles? They are moving much slower and do not have the outbound force to contend with. However, they do have a slight differential force applied to the outside hemisphere, so they migrate also.

There is always a greater pressure difference at the poles of a fast spinning object than at its equator. As this differential grows, a slight flatting of the poles occurs. The faster the object spins, the thinner the once spherical’s poles become until the superforce punches through and the object takes on a doughnut shape. It is a torus. Superflux passes through the poles and carries all the electromagnetic information in two highly focused directions. Such is the operation of a neutron star and a black hole of a Quasar.

A gyro’s poles form two cones as it undergoes precession when a torque is applied. In the case of a humongous black hole, there isn’t enough matter around to apply much of a torque. A Quasar may be in the process of pointing its laser in another direction, but earthlings won’t detect the movement for generations of astronomers. But if a neutron star’s neighbors can apply enough torque to induce wobbling poles, every time the beam passes Earth it will generate a signal. The timing of the signal depends on how the cone’s ellipse points in our direction and the speed of the beam around that ellipse. If the angle of precession is 90 degrees, the signal hits Earth twice per revolution because there are two poles.

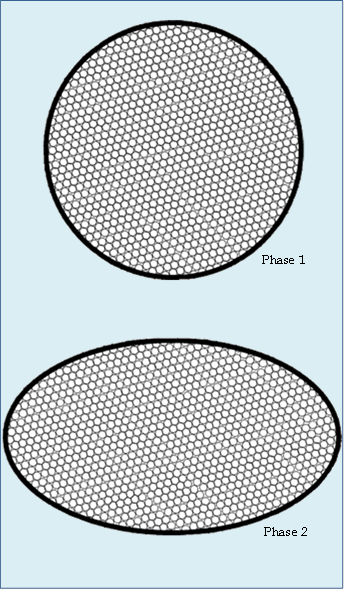

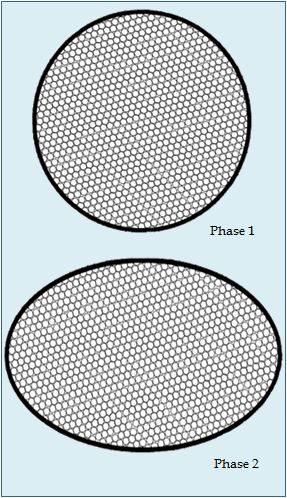

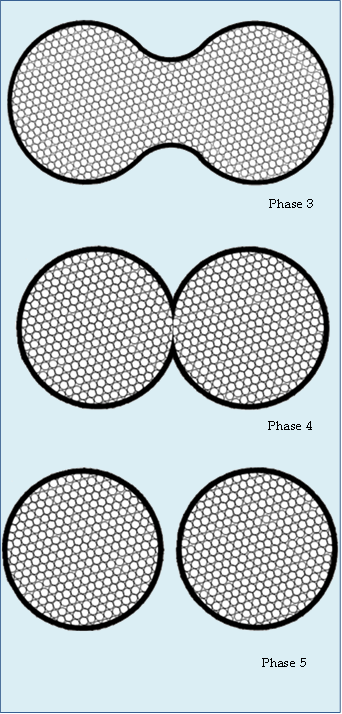

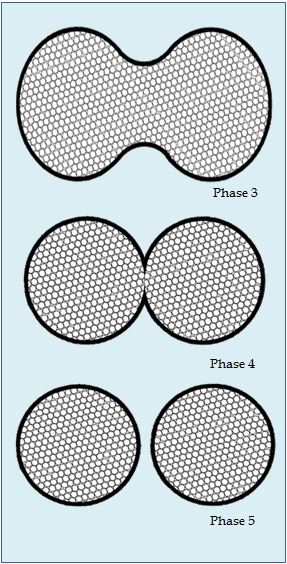

This experiment requires the use of ball bearings to emulate neutrons. The image on the left represents a small object filled with such. It is a sphere with little or no spin.

What happens when the object spins extremely fast—so fast that its matter spreads away from its axis of rotation?

Images Phases 1 thru 5 show the five possible phases as a neutron star flattens and potentially ends up as a torus.

At Phase 1, the object has not begun to spin at a high enough rate to contract, so the change is in pause waiting for shrinkage to begin in earnest. It only begins to flatten at a certain rotational speed. However, sometimes after the supernova starts to crush the once massive star down to a smaller object, it must increase its rotation rate at some point.

Somewhere near ten to twelve miles wide, the object has gained enough speed to send the balls outwardly, and as it shrinks even more, it must spin faster. Phase2 shows how the ball bearings have migrated outwardly while the superforce has flattened the poles.

At phase 3 the bearings continue to migrate away from the center leaving less resistance to oppose any forces at the poles.

At phase 4 the superforce is ready to push through the poles and carry information in both directions. However, the greatest release of magnetic energy probably happens just as the torus moves from being a horned torus to a ring torus at phase 5.

The image on the leftabove is a neutron star that has spun itself to a point where the superforce has broken through but the torus has not opened.